Rebel Justice

What is justice? Who does it serve? Why should you care?

When we think about justice, we think about it as an abstract, something that happens to someone else, somewhere else. But justice and the law regulate every aspect of our interactions with each other, with organisations, and with the government.

We never think about it until it impacts our lives, or that of someone close.

Our guests are women with lived experience of the justice system whether as victims or women who have committed crimes; or people at the forefront of civic action who put their lives on the line to demand a better world..

We ask them to share their insight into how we might repair a broken and harmful system, with humanity and dignity.

We also speak with people who are in the heart of the justice system creating important change; climate activists, judges, barristers, human rights campaigners, mental health advocates, artists and healers.

Rebel Justice

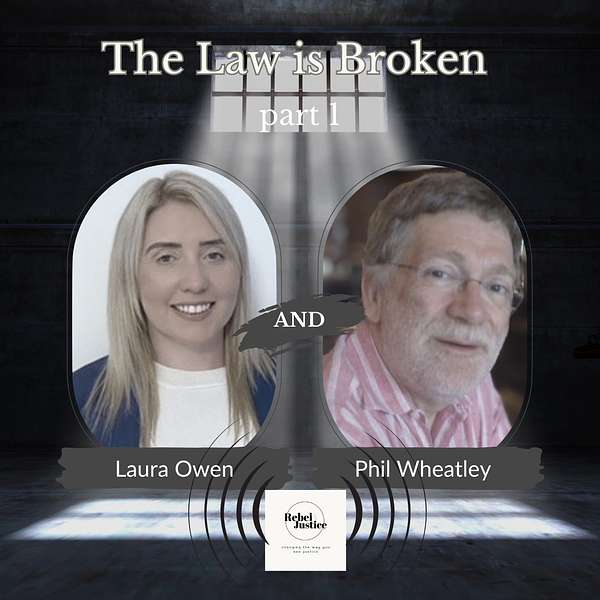

53. The Law is Broken - Unpacking The Challenges of our Growing Prison Population with Laura Owen and Phil Wheatley (Part 1)

Part 1 of 2 Join us for an enlightening conversation with Phil Wheatley, a veteran of 50 years in the prison system, and Laura Owen, a dedicated prison lawyer with 14 years of in-depth experience. Their expertise promises to provide you with a rare and comprehensive insight into the murky intricacies of the prison system. In our discussion, we zoom in on the frequent use of the 'being of good behaviour' licence condition, a term that has become an easy tool for recalls and subsequently, a major contributor to the backlog of parole cases.

Together, we unpack the policies that are fuelling a surge in our prison population.

As we continue to dissect the prison system, we draw attention to the growing pressure on probation services, a byproduct of the rise in the prisoner population. Phil and Laura explore the challenges of staff recruitment and retention and the arduous process of enforcing licence conditions. Our seasoned guests also touch on the importance of an effective engagement between probation officers and prisoners in reducing reoffending rates, highlighting the necessity for a comprehensive approach to rehabilitation.

Finally, we approach the contentious topic of privatization within the prison service. We dissect the government’s motivations behind this shift, and how it has fundamentally impacted the prison system. From the pursuit of cheaper prison running costs to the impact of funding cuts on the roles of prison officers and rehabilitation opportunities, we leave no stone unturned.

In conclusion, Phil and Laura weigh in on the effects of privatization in the prison system, the challenges that have arisen and the far-reaching implications for access to justice, parole, and rehabilitation. Tune in for an impassioned discussion on the state and future of our prison system.

For more unmissable content from The View sign up here

Episode 52: The Law is Broken - Unpacking The Challenges of our Growing Prison Population with Laura Owen and Phil Wheatley

Rebel Justice – The View Magazine

Season: 3

Episode: 52

Charlotte White, host: 0:00

Welcome to the View Magazine's Rebel Justice podcast. In this two-part episode, we're exploring issues in the prison system and how they're affecting those on both sides of the law. With increasing legal fees and the rising cost of living, access to legal advice is becoming difficult for many people to obtain. Couple this with year-on-year justice funding cuts and a drastic reduction in legal aid provision and you have a strained and overloaded system that’s struggling to cope, and the impact on the justice system has been dramatic. Since 2010, 239 courts have been closed. That's 43% of all courts. Cases are not being heard, meaning a huge backlog of cases and prisoners waiting sometimes years for their case to be heard. Unsurprisingly, a 2023 government report found that 80% of prisoners feel that morale is poor and they are underpaid for the responsibilities that roles entail, and the legal representatives are also under pressure. There are now 58 local authority areas without a practicing barrister and 393 constituencies without any legal aid barristers. To explore some of these issues further, we're joined by two experts who've spent their careers in the prison system. Phil Wheatley started his career as a prison officer in the 1960s and, over the years, has held numerous positions within the prison service, from prison governor right up to director general of the government agency responsible for the prison and probation service. Laura Owen is a prison law consultant with expert knowledge in all aspects of prison law. She often works on complex parole cases which can involve prisoners with additional challenges, such as mental health issues, behavioural issues or learning disabilities. In this first episode, Phil and Laura talk about their vast experience of parole, probation, access to justice and the current backlogs that are leaving people stranded in the system.

Alex Bastien: 2:03

Good morning. My name's Alex Bastien and I'm here interviewing two very experienced professionals. On that basis, I will hand over. Phil, would you just introduce yourself first?

Phil Wheatley: 2:15

Yeah, my name's Phil Wheatley. I've spent most of the last 50 years and a little bit more working on prison issues. I joined as a prison officer as I left university in 1969 and then worked my way up through the system, becoming a governor in 1990 and then into various headquarters jobs. For a bit, I was in charge of the high security prisons in the aftermath of a series of rather disastrous escapes, trying to improve things. I then took over the sort of operational management of the prison service, again in the aftermath of a series of very rightly critical inspections from Lord Ramsbotham, with a brief to try and sort things out, which I think I achieved, though it's not an easy task. It was a long slog. And then I became Director General in 2003 of the prison service and in 2008 Director General of NOMS, which is now HMPPS and Prison and Probation Service, and I retired in 2010, aged 62. And I've then been working on prison matters ever since, mainly either being a trustee of a charity involved in work with prisoners, currently an education provider works in prison and expert witness work on litigation and deaths in custody, mainly in Scotland, fatal accident inquiries, acting for the Procurator Fiscal, giving expert witness evidence for sheriffs to consider.

AB: 3:43

And our other guest today is Laura Owen. Laura, would you mind introducing yourself, please.

Laura Owen: 3:48

Morning. I'm Laura and so I'd always been interested in law, criminal justice system, and I studied law at college and then went on to study criminal justice in uni. I was quite lucky that I fell into prison law through a family friend and she basically trained me up. I really enjoyed the job. Really enjoyed meeting different people and just trying to help people. So, I've now spent nearly 14 years as a prison lawyer.

AB: 4:13

Fantastic. Just tell us a little bit more what it means to be a prison lawyer. What kind of aspects of the job would you kind of come across on a day-to-day basis?

LO: 4:22

So, prison law is quite a niche area that not many people are aware of unless they're involved in the system, and so prison law mainly covers parole hearings, adjudications. So day-to-day I would spend my days representing mainly life sentence prisoners, IPP prisoners, assisting them with the parole process, parole board reviews, and then I also deal with adjudications. So, if, mainly young offenders, if they've breached the prison rules and are up in front of a judge, I would assist them and provide them with advocacy assistance during that process as well.

AB: 4:57

Fantastic, and I suppose today we're really talking about access to justice. We're talking about the struggles of all these different aspects of probation: prison lawyers, governors in prison, security staff, all sorts of people and how it all comes together, how the system runs and what the challenges of the system are and what can be done to facilitate things. Which direction are we heading to in terms of the future? Is it improving or are there some concerns that we can talk about? But I think, in terms of both of your broad spectrum, in terms of what you deal with and your experience, I think we can cover across quite a few issues. Let's talk about the criminal justice system as it is at the moment, and I think we'll go a little bit further back after that and discuss how it may have been in the past and whether more positive or negative, and how it will be heading and in which direction it will be heading in the future. So, where we're at at the moment, Phil, how does it compare to where it's been, let's say, 10, 15 years ago?

PW: 6:03

I mean I've never seen the criminal justice system in such a bad state in the whole of my career, with a backlog of now 60,000 cases plus waiting for crown court, with defendants who have been remanded in custody spending maybe up to two years in custody before they reach trial. That's never happened in the past. And there are not only other prisoners in prison awaiting trial, there are lots of people out on bail awaiting trial and they tend to take even less priority because they're on bail. So those cases are being dealt with well after the events that cause them. Witnesses have forgotten, can't give clear evidence. It means that victims aren't receiving justice. Those who are wrongly charged and are innocent aren't being cleared properly. It is a total mess and a product of the pandemic a bit, but not much. The major impact has been the withdrawal of funding from all the players in the system, so the police lost resources and shed many of their experienced detectives. The bar hasn't had a reasonable pay rise for a long time, so people aren't going into criminal law and there's a shortage of criminal barristers. The courts are decaying a bit like schools are, and regularly going out of use or leaking and things breaking down. This isn't how a sophisticated Western country should be doing justice.

CW: 7:32

Laura highlights the issue of increasing prisoner recall. Recall is where a prisoner who has been released is sent back to prison. It can happen if someone doesn't follow their parole conditions, fails to attend a probation appointment or if they're accused of a further offence. The particularly subjective licence condition which appears on all licences is to be of good behaviour and is an easy catchall for a lazy, overworked or malicious probation officer. Over 50% of recalls are due to alleged breaches of this behaviour condition, clogging up a prison and parole system that's already choking.

AB: 8:09

Laura, would you share some of that in terms of where you stand on your side of the fence?

LO: 8:14

Yeah, I completely echo that. It's a difficult one because we're seeing more people than ever recalled to custody. As Phil's just mentioned, cases aren't being heard by the court, so people that have got new convictions can't get their case heard by the courts, which then means parole boards can't consider their case because of the ongoing criminal matter and the parole board system in itself at the minute is again a complete mess. We actually saw a decrease in backlogs during the pandemic because everything became remote, but then when all the policies changed last year, we have now just seen a significant backlog. Probation officers weren't able to direct release on the papers. The justice secretary stopped people going to open conditions and started changing his own mind on previous decisions. So, we've now got thousands of cases waiting to be heard in front of a parole board that can't be heard because of ongoing police matters or criminal investigations and just because of the significant backlog, because there's just not enough panel members to hear the cases.

AB: 9:14

So, I suppose we're dealing with a new challenge. Phil, would you say this is something that you've experienced or has been overcome in the past by previous governments or organisations?

PW: 9:23

No, the thing that is new is that governments in the past were very keen that the justice system worked well and really they relied on the parole system to select people for early release, which helped keep the prison population under control, which most ministers, for most of my career, had as one of their policy objectives not to have too many people in prisons, very expensive to keep people in prison and really. Beginning in the mid-90s when the two political parties began to vie for ‘mirror mirror on the wall, which is the toughest of them’ all in the hopes they get votes, that's Tony Blair's period as shadow home secretory, really and then exacerbated times 10 by the approach the current government and the coalition government took to being tough on crime. So, for instance, all the things you're coping with in the parole field are a result of the minister wanting to prevent people get parole. I mean, you can put whatever spin you want on it, that's what it amounts to. He really didn't want people, particularly famous people who the media might know, to get parole and trying to prevent that happening. And so, we are in quite unusual circumstances. We have never had such populist policies being pursued by all the parties. I don't want to be party political about it because nobody's speaking the language. It would have been common enough for both parties up until the mid 90s.

AB: 10:51

How are the government dealing with that? I suppose there's more pressure on prison services. Has there been more funding? I know the answer to that, but I'll let you both give me the answer and give that answer to those listening.

PW: 11:06

I know the facts on it. The coalition government introduced cuts of 20% in prison service funding and probation service funding, the non-funding as it was. They've reinstated some of that because plainly they'd gone too far. So there's now 10% less funding than there was as the coalition government came in in 2010, as in real terms, adjusting for inflation, and that's getting worse all the time as inflation is eating into what the money will buy. So that figure was accurate two or three months ago. The government has been allowing the prison population to build and they've done that by encouraging longer sentences for crime and greater recalls and putting more and more people out on licences. Now nearly everybody gets out on a licence, which means they're eligible for a recall and they're seeking to recall rather than to run a risk and try and help somebody. That's the general approach. And a probation officer who misguidedly decided they were going to overlook something because it was in the best interest of the long-term rehabilitation of the person they were working with. If it went wrong, they feel they would be crucified by the media and by their bosses and by ministers, and they are right to feel that. So, they're very risk averse, which is fuelling the recall of a larger number of people that might otherwise have been the case. It's not being a helping service. It's now sort of policing and checking service for many people. It's not true of all probation officers, but they're under pressure to behave in that checking and policing approach rather than a helping and caring approach. So that's driven the population up and roughly. Compared to when I joined in 1969, sentences are about double in length. What you would have got for the same sort of offence in, and 1969 wasn't a wildly liberal period in penal policy, but we've about doubled sentence length, and for lifers, I would have said to a lifer in the early 70s, the chances are you'd do about 10 or 11 years. Now the chances are you'd do about 20 years. So, we've roughly doubled the length of life sentences too, and still we haven't got them long enough. So, the criers always give longer and the politicians fighting for votes are inclined to think we should give longer. Unfortunately, the police have also been under pressure and become less effective at catching people. They're catching fewer people, so the amount of people, for instance, convicted of burglary against the number of offences is about halved since 2013. But when we do get people, we then give them a very long sentence. That means a storage space, which is what prisons are, is full and overflowing.

AB: 13:52

Laura. I mean, obviously I'm not going to ask you for your advice on specific cases, but in general, do you find that what Phil just described to us, does that form part of your general advice to your clients when you meet them for the first time?

LO: 14:08

Yeah, particularly in relation to recalls. We are definitely at a point where recall seems to be the first option, where it was always supposed to be the last, and it's difficult because nobody's held accountable either. In cases where people are wrongly recalled, people lose a year of their life, their liberty, and nobody's held accountable. So, probation, don't mind doing it, don't mind recalling people because nothing happens to them either way. Even if it's agreed by the end of the process that the recall wasn't justified, nothing happens. So that's why they keep doing it. That's again why recall rates are so high because there's no accountability in cases where people were wrongly recalled. Yet somebody's lost a year of their life, their liberty, potentially jobs, employment, accommodation, and that seems to be where we're having the biggest struggles with people. And it's demotivating for a lot of individuals as well, when they are recalled when they've done everything correctly, to find themselves back in the system for having done nothing.

AB: 15:06

Talk us through that a little bit more, Laura. You would make the application, you would see what you would think as an unfair recall, you'd make your representations, I suppose, to prison and probation services.

CW: 15:21

Laura explains that one reason for cases being delayed is the end of executive release. This was where a release was ordered by the Secretary of State or the case worker on their behalf, without needing a parole hearing.

AB: 15:33

If that gets knocked back, if I can put it that way, what can you then do?

LO: 15:37

So, the process at the minute is a lot more difficult than it ever has been because executive release was taken away last year. It has recently been brought back in. The situation we find ourselves in now is somebody will be recalled to custody, the case will go straight to the parole board, whereas in the past the Secretary of State would have looked at the case first to see whether the recall was justified. So now we're waiting for a parole dossier, a recall dossier, to be prepared. We then prepare representations on the client's behalf, basically saying that the recall wasn't justified and his case should be reconsidered immediately and really should be redirected. We're in a position where the parole board were then unable to make decisions on the papers, so we're sending all the cases to an oral hearing. So in a lot of cases, they're still trying to work through the backlog and trying to prevent people getting oral hearings as well, which really is the easiest way for the client themselves to get their point across and there's a chance to have their say verbally. We can still apply for an oral hearing, but with the backlogs at the minute we're waiting about three, four months for the case to be considered on the papers if we're lucky. For it to then be knocked back, to then appeal it for an oral hearing, for us to then wait about 9 to 12 months for a person to get a hearing following on from that. So, there are options available, but it's not an overnight process. It takes months and is taking 12 plus months at the minute for a case to be considered and for the individual to have their chance to put their case forward.

AB: 17:02

And a question to both of you: does that vary from prison to prison? Is there a difference between female prisons, male prisons, different category prisons, different prisons in different parts of the country, privatised prisons? What would you say to that?

LO: 17:17

In my experience, no, because the parole board is national. They don't tend to work on prisons or region basis anymore. It's just the case of them getting through each case as it comes in and then just joining the backlog. So, in my experience, no, it doesn't matter where they are. If they're female, male, they're just stuck in the system until the parole board can hear the case.

AB: 17:40

So, the issue is with the parole board as opposed to prisons or probation services? Is that right, Phil?

PW: 17:46

All the various services playing in this are all under pressure. They're all probably not adequately resourced for the amount of work they're doing. The probation service in particular cannot and hasn't been able until very recently to recruit and retain new staff. They've been losing them to better paid jobs. Many of them have gone into youth justice, for example, which is still quite a good system operating with rather more resourcing. So all of them are struggling. But I think it is a national system is paroling and therefore it doesn't affect individual prisons differently, only as far as how many recalls have they got in their particular prison, rather than the length of the queue. Maybe different prisons? I think the queue is run nationally and misery is shared.

AB: 18:34

Just a little bit more on probation, and I guess it's never good for me to try to in a few seconds explain what a body like that does, but I suppose for those listening probation’s involvement would be usually from the point of conviction of defendant in a crown court, magistrates’ court case, where they would help to write a report to the judge to suggest what type of sentence could be best or what they would provide the court with is some background information for that defendant and then they would follow it through. So they would assist in supervision if that defendant ended up on a non-custodial sentence. Or they would help with rehabilitation or the whole process in terms of custody until release and then the license period. Is that roughly a good description? Or please help me out and provide a little bit more if either of you would like to.

PW: 19:30

Okay, and that's, that's historically what the probation service have done. But we, those of us at the centre and I include myself in this, cause I was in charge of the probation service, albeit briefly, and now some time ago, but ministers became increasingly concerned from Michael Howard onwards that the probation service were just helping offenders and weren’t holding them to account, and that they were properly punishing people who were doing community sentences, which were meant to be punishment. And you can see that in the badging of what originally was community work and then became Community punishment in order to emphasize to the public this really was a form of punishment and the emphasis on making sure that people actually did what they were supposed to do, all perfectly proper. But that's split over into ordinary probation work as well. So when supervising somebody and trying to encourage them and help them to be successful on release or on a community sentence, the pressure came on the probation service to be very rigid about that tick box approach. Have you seen them within the first whatever it was four days of them getting an order? Did you see them once a week for the first two months and then you're allowed to relax it a bit. It was all to do with were you complying, rather than looking at the quality of the relationship and there’s some interesting work just published by the probation inspectorate, who are a force for good in all this and have been doing some really good inspections over the last seven or eight years in particular. Very impressive. And they've done a detailed piece of research looking at how good quality engagement, really good quality probation work, what effect does that have outcomes, both reconviction and how fast it takes somebody to fall back into crime, how long do they manage to stay free and found that where you can see really good quality engagement, an individual probation officer who's engaging properly with somebody, probably concerned about them, not soft on them, but having a relationship that's positive. That produces I think the figures are something like a 14% reduction in what you would otherwise have got by way of rate of reoffending and the delay, people stay crime free longer, even when they do fall back into crime. So it looks like the old way of working if it could be encouraged more and get away from a tick box enforcement culture does actually pay off in reducing reoffending.

AB: 21:57

And I suppose for the taxpayer it would be cheaper for someone who's gone through the court system to be under probation as opposed to be in a prison setting. Is that also accurate?

PW: 22:07

That's probably right, though good probation isn't cheap. Prison is always expensive and if it depends on the trade office, is somebody was gonna get a seven day sentence and that was going to be it, that's cheap in prison versus a two-year probation order. And if they were going to get a two year sentence, they get a two year probation order the probation is cheaper. So you can't do an easy, just a straightforward, it's cheaper, but it certainly requires a lot less capital. You don’t have to go and build a whole load of new prisons, which is what we're doing at the moment, and it may do a lot less damage to people, because if you've got a job and basically you're doing okay, but you commit a crime, because people tend not to get out of crime, they start to give it up and they hiccup along the way. It's been like giving up smoking, where you probably manage it the first time and then you fall by the wayside. Then you try again. That process of trying to encourage people out of crime and accepting that they'll fall back into it from time to time. But trying to get them out is important and if you constantly send people to prison, you make it much more difficult to stay clear of crime because you've disrupted family relationships. They probably lost a job. They may have lost the flat they were living in and come out homeless and a whole series of things that will make it more difficult to become free of crime, having come out from prison, rather than having been left with supervision in the community and just giving them a second chance. But we're not very forgiving as a country. We're not into second chances. We’ve become much more punitive as a country and if you look at the state of media, social media and sort of comments made, you can see how much people feel that punishment is the answer, although there's no evidence that a lot more punishment makes a big difference, if any difference, to the rate of crime.

AB: 23:54

Laura, I suppose you were saying that when you started off you basically fell in love with the job. There was a passion there for it. Do you find now that you're seeing these challenges, you're becoming more demoralized and losing some of that zeal, that passion?

LO: 24:09

To an extent, yeah. there are times where when things have changed recently, especially when we were talking about funding before, prison law hasn't had any increase of funding and we took the 10% drop in 2012 and haven't had anything back since. So we're working on fixed fees. I can end up doing 10 hours of work for a client and get paid for four hours of it. Then, when you're just getting knocked back at every angle, it can be frustrating. It can be very difficult. You're trying to help people. You get everything in place for the client, the individual, they get released, and then the things that were promised from probation weren't put in place. The support wasn't there. The access to section 117 aftercare is not there, and then people get out and struggle. It's demoralising when you're trying to do everything you possibly can to give people the best chances. People sit on hearings promising everything to assist the individual and then it's not given and then the individual's just recalled. That side of it is really demoralising.

AB: 25:07

When you find you're having conversations with probation officers, prison staff, etc. Do you find that there's demoralisation across the board and that kind of continues, this kind of domino effect?

LO 25:21

Yeah, again because of the lack of resources, you get certain individuals that are really trying to help the clients and trying to put things in place and just don't have the resources to do so, and some just don't have the time to put things in place. This is something again that's causing problems across parole board. Community offender managers just do not have the time and the resources to make sure things are in place beforehand, so probation are frustrated that they've not had the time to get things in place, which then knocks onto the parole hearings being delayed for them to have more time. But there's just not the resources, there's not the staffing, there's not the funding and again, everyone just feels at the minute that they're just paddling and sinking as opposed to helping people and moving forward.

CW: 26:05

Laura explains her concerns about prisoners on IPP sentences. IPP stands for Imprisonment for Public Protection. These were specific sentences given to people who were considered a significant risk of harm to the public. IPP sentences were ended in 2012, but there are still people in prisons serving them.

AB: 26:24

And speaking of that, I suppose again generalisation, but I'm trying to cover quite a lot in a short space of time. The clients you're dealing with would be relatively vulnerable. I guess you'd agree with that. Good and, in that sense, with them seeing all of this, how do they take it? Because they are people where you're trying to say to them, look, trust the system. You know, we're fighting for you. All the right people in the right places, doing what they need to do to ensure the right outcome for you. That's what you'd like to say, surely? But I suppose, since you're not able to say that what's their response? Where does their motivation lie once they hear what the real crux of the matter is?

LO: 27:05

I think this is where the main kind of issue comes with a lot of IPP prisoners. It's that lack of hope, frustrations. People just can't stay motivated because actually staying in custody is easier, where they have access to everything they need, because they can't get it in the community.

AB: 27:21

Sorry. Would you just mind explaining what IPP sentences are just a little bit more?

LO: 27:26

Sorry so IPP sentences, many will probably have heard on the news were sentences brought in for what was seen as the most dangerous in society. So it stands for imprisonment for public protection. And we would find somebody would be given a minimum term of, say, 16 months but they can't be released until a parole board then sees them fit to be released some years over tariff. I have individuals at 15, 16 years past their minimum term purely then because they've got stuck in a system of the hopelessness, the frustrations. Many have had previous childhood trauma. They can't address that. They then use alcohol or substances to try and mask that and then find themselves stuck in a system where they can't get released because of issues that they've encountered in custody.

AB: 28:17

Phil, you touched upon good work being done by organisations to highlight the issues that are being faced day in, day out by practitioners such as Laura. How is the government responding to all of this good research?

PW: 28:36

The government are doing very little research and the sad truth is that the government, as I've seen it, has been very reluctant to invest in research. It might prove that their political ideas aren't very effective, so you shouldn't expect ministers to have much enthusiasm for spending a lot of money on research that inevitably is long term because it’s trying to work out what the impact of various interventions are, requires you to wait long enough, one for people to get out and two for the police to catch them and the courts to process them. So before you can get a reasonable sized sample of lots of proper evidence, you've probably got four or five years. Well, a Secretary of State with precious little money, as they see it spare it, doesn't really want to invest in that long term investment that’ll pay off for a future Secretary of State maybe, or could have the effect of proving that what you were doing was wrong. So why would you want to do that? So there is money spent on stats and basic research, but it's mainly fuelling the requirement that the department has for statistical information, rather than the sort of research that the old fashioned Home Office Research Unit used to manage to university standards in the 70s and the very early 80s. So I think we're not going to learn much from officially sanctioned research. There's some approved research from outsiders. For instance, there's lots of work being done by the Cambridge Institute of Criminology, which I declare an interest in because I'm on that management board so I know what they do and I've worked with them over the years. But they've done some really good quality work in prisons, understanding how prisons work, and some of that's been funded by research grants rather than by the ministry, and we those of us who ran the prisons were keen to get external research in. We liked research and we liked the product of it and we thought that we could do better if we looked carefully at what that product was. But we haven't much we could invest ourselves. What we had, we did, and we certainly tried to facilitate access, but often, again with political concerns, the research was likely to find things that were politically embarrassing and in a combative system with two parties trying to score off each other, I see why Ministers are worried about that.

AB: 31:05

And whilst we're on, the government's input into the prison service privatisation, and I've obviously seen a lot more movement in that direction, more privatised prisons. What do you think the motivation has been from the government as to why there's been more of a shift towards private prisons?

PW: 31:27

Right. The motivation has been quite complex and has changed over time, depending on how the government's accounting rules work. As much as anything else. If we go back far enough in time, and I'm speaking really about the mid-80s, the prison service was dominated by a very powerful union, the prison officers association, who very often worked not only hard to get their members lots of money but to prevent change, because prison officers are always wary of change because they know today works and when some bright spot like me comes along saying hey, we can do this differently, they're not sure it's going to work. And so there's a sort of inherent bias against lots of radical change. But lots of good change was being stopped and staffing levels were being driven up fairly aggressively in order to get more money, because it was an overtime culture. Then there was money made by working more hours, and that power of the union was the thing that held back lots of progress. That stopped being true really by the mid-90s, and part of the reason why it stopped being true was because the government were prepared to use the private sector, and so prison officers in the public sector realized they couldn't carry on having a monopoly of provision if that was bad provision done very expensively, and the private sector opened some quite good prisons that worked rather well, that were reasonably well funded, because the government wanted this to work, and so alt-course was a very expensive private sector prison but a very effective private sector prison. In its early start-up period and for most of its time actually, Doncaster had a difficult start-up but then became pretty good, and so you could see that private sector prisons had introduced changes, showed that some reductions in inflated staffing levels were possible, that a different approach could be taken to working cooperatively with prisoners. And so the private sector played a positive role at that point. My view always was that some competition is good for everything. Too much competition has people obsessed about competition and you give too much power to a private sector making money, so it becomes the dominant provider. It's in danger of skewing your criminal justice policies and inflating its profits, because that's what a good private sector operator tries to do, nothing wrong with that. And so a mixed economy with a bit of competition made sense. The government was also keen on it because the money that the private sector borrowed to build prisons was regarded as not public sector debt, and so it made the books look better. It was still money borrowed to build a prison and borrowed quite expensively because the private sector has to pay more to borrow money. Once that accountancy change was made to say, hey, this is daft, it is public borrowing. It's public borrowing in a different form that became a less attractive option for the private sector to borrow expensively when the public sector could borrow more cheaply. So that removed some of the government enthusiasm for using the private sector, and then we probably had a period recently when the government sort of had a vague feeling the private sector was always better and then made the mistake of buying some very cheap contracts, forcing the private sector's prices down aggressively as part of austerity, which meant the private sector had to cut their staffing levels, keep their wages very low and run into the same problems that now the public sector prison service is having. You don't pay enough, you don't get good quality people and you don't retain them and you don't get enough of them. And if you don't have enough staff on the landings for prisoners to be confident that staff are in charge and they aren't, prisons can become anarchic and dangerous places, and so the pursuit of cheap prisons in both public and private sectors has destabilised prisons. So if you look at a prison nowadays, compared to when I was working in 2010, as a member of staff, you’re three times more likely to be assaulted than you were when I left. That's 13 years. That's a really enormous increase in risk, and as a prisoner, you're twice as likely to be involved in violence between prisoners. So your chances of being hit and hitting somebody have both increased by a factor of two, and self-harm rates have about doubled. So you're much more likely to injure yourself, and that's, to a large extent, a consequence of reducing funding, shedding experienced staff, reducing staffing levels and then finding the new, cheaper staff don't stay as long as the older, better-paid staff did and never developed enough experience to be as confident as the best of experienced prison officers were, because you've got some really, really skilled work by prison officers who knew what they were doing. Who were really good at dealing with people, but learned to do it better over the years, and that includes myself in this. AS a 21-year-old, I wasn't very good at it. By that time I was 25, I was quite good, and if I'd left then and gone and done something else, you'd have lost a lot of knowledge I'd built up and been able to use it over the years.

CW: 36:46

And that concludes part one of our insider's view into some of the issues facing the prison system today. Next time, Phil and Laura will be talking about how their roles have changed and evolved over the years and the impact the funding cuts have had on prisoners' opportunities and rehabilitation. Rebel Justice podcast is produced by the View Magazine. You can subscribe to the View at theviewmag.org.uk and follow us on social media. We are Rebel Justice on X, formerly Twitter, and the View Magazine on Instagram, LinkedIn and Facebook. Thank you.